Originally published in 1980, Suzanne and Louise tells the story of two sisters—one widowed, the other never married, recluses in a hôtel particulier in Paris’s fifteenth arrondissement. The author, who is also their great-nephew, is one of the few who visits them.

Suzanne takes a certain pride in having risen from the poor, uncultured working class to her position as the wife of a well-to-do shopkeeper, in having completed her studies and become a musician, after having traveled far and wide, reading Proust and listening to the “great works” of music. Louise respects this accession (her exclusion). “I quit after elementary school,” she says. Before entering Carmel, and then working at the pharmacy for her brother-in-law, Louise worked in Rheims for an insurance company. Louise loves frothy things: sparkling wines, sentimental magazines (on her bedside table, Nous Deux is next to Catholic Life), operetta music.

Ten years separate Louise and Suzanne. They were not raised together. And yet they share the memory of a poverty-stricken childhood spent in the country, with a railroad switchman father and a mother from a penniless bourgeois family.

Louise does everything: the cooking, the laundry, the cleaning, the shopping. It’s she who dresses and bathes the partially disabled Suzanne. The water she throws on Suzanne’s body is always too hot, the food she serves her overcooked and cold. The pair of scissors she uses to clip Suzanne’s toenails often cut into her skin.

Not necessarily in “narrative order,” some minor events that end up disturbing their daily routine: a bell ringing, a bad dream, the dog dying. Suzanne refuses to take her daily walk for no reason. Louise overhears her talking to herself. Suzanne pays Louise, very little. Louise is her only heir. Louise puts her salary in the collection box during Mass. She squanders her money on wine and wishful thinking. No one will ever know why Louise entered Carmel, forty years ago, and why she left, eight years later.

The play.

One Sunday, behind Louise’s back, Suzanne says to me, “That play that you wrote about us, I’d really like to read it, after all.” She asks me to bring her a copy the following Sunday, and to hide it underneath my blazer when Louise comes to let me in, since she thinks Louise won’t appreciate it. When I hand her the stack of stapled photocopies, she immediately hides it, without even looking at it, in a drawer of her bureau, saying, “If I die in the meantime …” Suzanne never calls me, out of a concern for saving money, perhaps, or for fear of bothering me; I’m always the one who calls. But that Monday evening, as soon as Louise has left for Mass, Suzanne telephones me, and in a trembling but determined voice, says:

“My heart is racing. I already tried calling you last night, but you weren’t home. So, listen, you might not be happy about this, but you’re going to have to change some things. First of all, our names aren’t Louise and Suzanne, our names are Hortense and Patricia. We don’t live in a mansion in the fifteenth arrondissement, we live in an apartment in a modern building, next to the Jardin des Plantes. We didn’t used to be pharmacists, we ran an old hardware store. Also, change the dog’s name, Whysky is too specific, someone might recognize him. Call him something like Sardanapalus. You say that I took a hundred francs from the drawer every day—you must be crazy! We’ll have the taxman after us. And then, that thing about the safe hidden behind a painting, you can’t keep that in, someone will come here and torture us until we tell him where it is, regardless of what’s inside … Take out that bath scene, too, it will hurt Louise’s feelings … You know, when I say all these things, it’s not for me, I don’t care, it’s for your sake, you know, you’re just asking for a defamation suit …”

Suzanne’s legs.

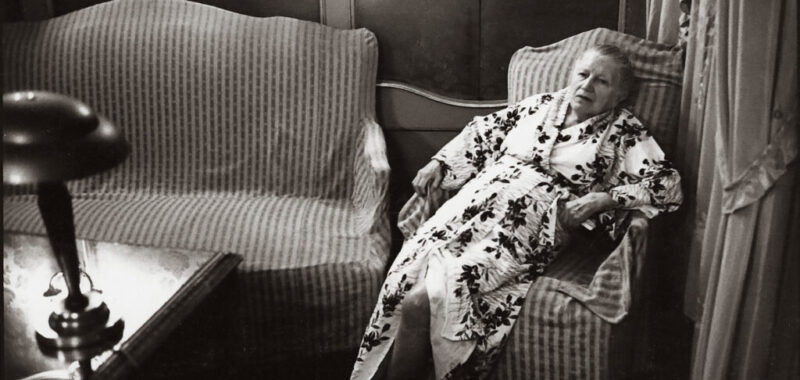

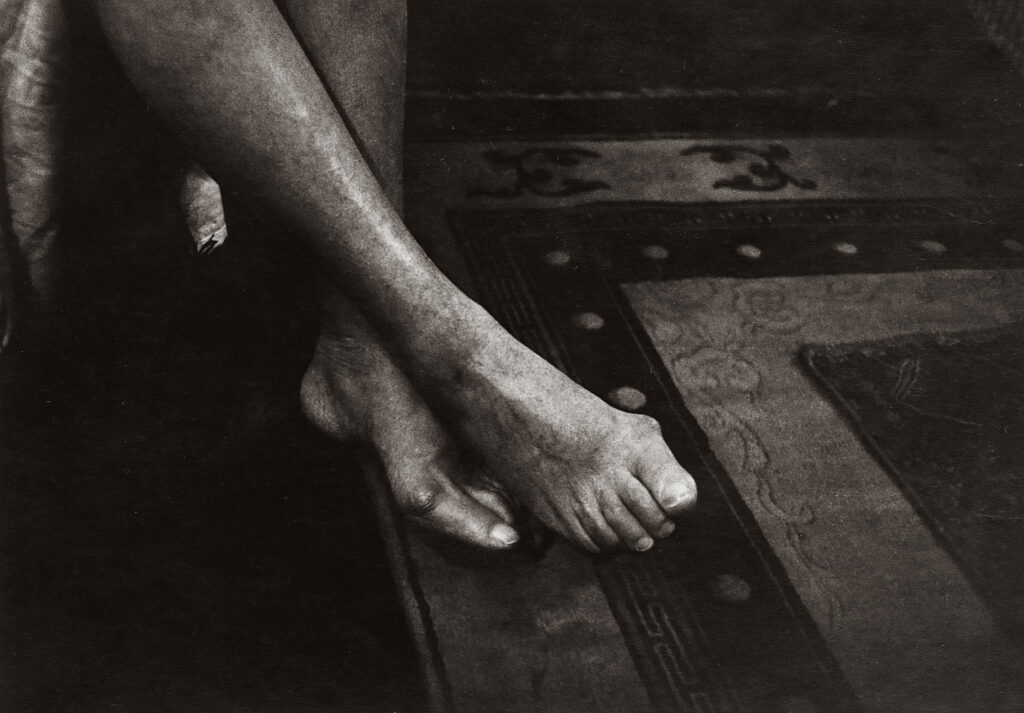

Today, for the first time, Suzanne allowed me to photograph her legs, at the foot of the sofa that’s fitted with a slipcover, she took off her slippers, she lifted her nightgown above her knees and said “Call the photo Legs of a Cripple,” and I said, “No, it will be called Suzanne’s Legs.” “Well, so much for my modesty,” she said. Next time, I’ll photograph Louise’s naked legs and feet, next to that huge bone with red teeth marks that Whysky chews.

Photography.

I think things other than lenses make “good photos,” ethereal things, of the order of love, or of the soul, forces that pass through and inscribe themselves, fatally, as the text that gets written in spite of ourselves, dictated by a higher voice …

From Suzanne and Louise, translated by Christine Pichini, to be published by Magic Hour Press in November.

Hervé Guibert (1955–1991) was the author of twenty-five books and published extensive texts and criticism on photography, primarily with the French newspaper Le Monde. His bestselling novel To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life was inspired by his close friend Michel Foucault and the two men’s experiences living with AIDS, which tragically ended Guibert’s life at the age of thirty-six.

Christine Pichini is an artist and translator based in Philadelphia.