December 17, 2024

2 min read

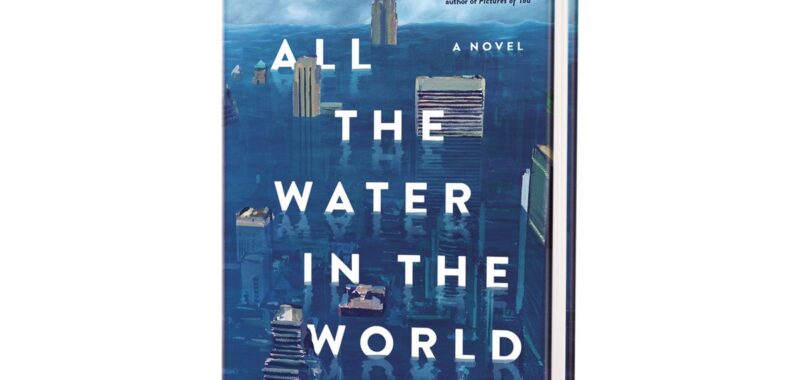

Book Review: In a Drowning New York City, Can All of Natural History Be Saved?

In the often-gloomy genre of climate fiction, a new novel hits a high-water mark for its empathy

All the Water in the World: A Novel

by Eiren Caffall. St. Martin’s

Press, 2025 ($29)

Eiren Caffall’s lyric yet gripping first novel centers, as its title suggests, on life after a great flood, with a young woman known as Nonie canoeing over a drowned New York City and up the Hudson River toward the high ground of the Berkshires. Fittingly for the genre of postapocalyptic American fiction, Caffall offers grand visions of the world made strange—Nonie sits in the bow of a canoe, watching the water for “snags” such as the tops of streetlamps or the trees of Central Park—and stirs suspense in encounters with the various settlements and wildlife along the route.

Like the cultural ephemera of Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, the seeds in Alison Stine’s Road Out of Winter or the child in the womb in Louise Erdrich’s Future Home of the Living God, a symbol of hope has been carried from the book’s fallen civilization to take root in whatever comes next. This time that symbol is natural history itself, as set down in a journal by former scientists at New York’s American Museum of Natural History. At the novel’s start, in a city that’s not yet fully flooded, those scientists and their families have formed a makeshift society on the museum’s roof. To protect physical exhibits that may not survive, they’ve taken pains to preserve the knowledge those exhibits represent in a logbook that, when the waters rise, will be carried in Nonie’s pack.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Like her scientists and survivors, Caffall relishes the museum and its treasures. Her vision of the institution stripped bare by desperate caretakers unsettles and moves. The novel is often dark, steeped in grief and uncertainty, concerned with practicalities such as infections and finding antibiotics. Caffall favors a briskly ruminative approach with short, reflective chapters about what life after the end feels like. (Violence, including threats of sexual assault, occurs mostly off page.) But that’s not to suggest that All the Water in the World neglects the beauty and wonder of Nonie’s adventure. The scene of her family floating away from the museum in an Indigenous canoe from an old exhibit is tense, delightful and rich with resonance.