February 18, 2025

4 min read

Contributors to Scientific American’s March 2025 Issue

Writers, artists, photographers and researchers share the stories behind the stories

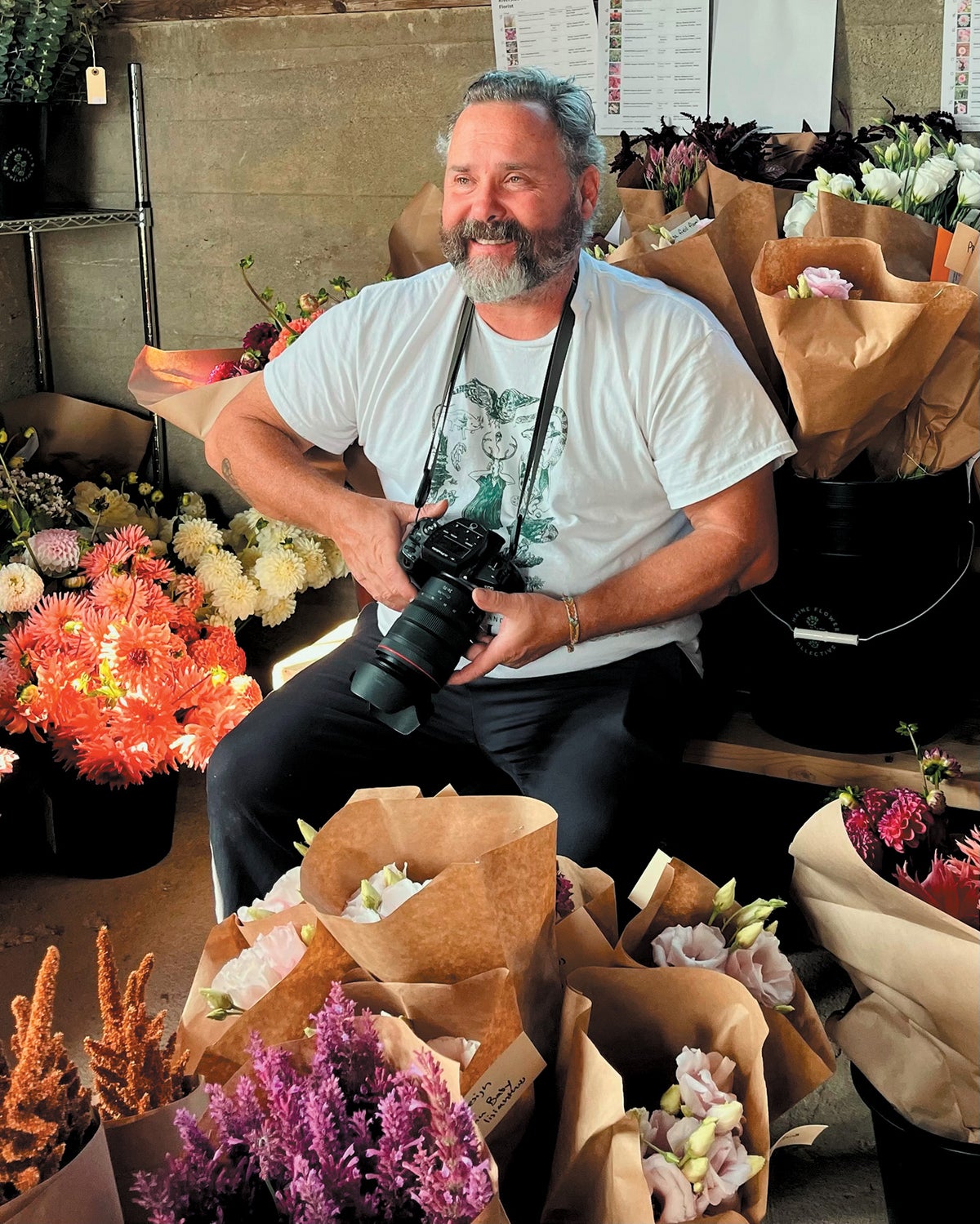

Jesse Burke

The Imperfect Bloom

For Jesse Burke (above), photographing a flower farm was a dream assignment. “When you send me to a farm,” he says, “you’re sending me to my favorite place ever to talk to my favorite people ever.” Burke felt a “kinship” with the Maine-based flower farmers he photographed for this issue’s story on sustainable floriculture, written by journalist and Scientific American contributing editor Maryn McKenna. He and his family have dubbed their home in Rhode Island “Sweet Bean Farm”; they raise chickens, potbellied pigs and pet Flemish giant rabbits (“imagine a Boston Terrier [in size], but it’s a bunny with giant ears”).

Burke’s photography often fuses the worlds of science and art. For this shoot, he brought a macro lens to get detailed photos of the blossoms’ structures. Close up, the flowers’ centers almost look like fireworks, he says. He specializes in something he calls environmental portraiture, or capturing people in nature, and is known for his photo series Wild & Precious, which documents trips to beaches, mountains, forests and canyons with his young daughter. This kind of photography is “sort of raw and wild,” he says. “It was a great tool for creating this relationship between my kids and nature and between me and my kids.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Maryn McKenna

The Imperfect Bloom

When journalist Maryn McKenna began living part-time in Maine, she became intrigued by the local flower growers at farmers markets. “I wanted to know how they make it work when there’s this dominant, incredibly lucrative and incredibly inexpensive product that sort of saturates the world,” she says. In her feature story for this issue, she investigated the harms linked to the perfect blossoms you might find at the grocery store, and she followed the movement of small farmers who are instead growing sustainable flowers with local character.

McKenna began covering public health in the 1990s, when she investigated cancer clusters surrounding a former nuclear weapons plant in Ohio. She’s learned an important lesson in her reporting: “Most of the time there are not villains in the world,” she says. “Most of the time people are doing things for what seem like good reasons at the time,” but their actions have unintended consequences, she adds. Take, for instance, the overuse of lifesaving antibiotics—the subject of two of her books—which has created legions of resistant “superbugs.”

The use of these drugs in flower agriculture has mostly flown under the regulatory radar. “We forget that flowers are a crop,” she says—and not a frivolous one. From funerals to weddings to holiday celebrations, flowers are often the centerpieces of our most important cultural traditions. “The beauty embodied in flowers is actually very important to our lives.”

Dakotah Tyler

The Missing Planets

As a Division I football player in college, Dakotah Tyler lived a life structured by his sport. Then he got injured. “Not having that passion and that purpose created sort of a void,” he says. But in its absence, a new fascination emerged. While watching astronomy documentaries, Tyler became enchanted by the idea of worlds outside our solar system. “I remember thinking that there was probably a planet made just totally out of glass and maybe one that was completely diamonds,” he says. Now finishing his Ph.D. in astrophysics at the University of California, Los Angeles, Tyler studies the mysterious rules that govern planetary formation, which he wrote about for this issue.

Exoplanet research is full of surprises. Take a class of planets called hot Jupiters, for example. At one time “we didn’t even think that those were possible,” he says, yet “they’re everywhere.” The mysteries still to be resolved by exoplanet research continue to capture his imagination. Even if the universe wouldn’t create a planet of glass, could it create one with frozen ice clouds blanketing an unreachable surface, like a fictional planet in his favorite movie, Interstellar? It’s not as far-fetched as it once seemed, Tyler says. Reality is often “much more complicated and much more interesting” than we think.

Jen Christiansen

Infographics

After graduating from college with degrees in geology and studio art, Jen Christiansen had a simple goal: “to not choose one at the expense of the other for as long as possible.” To this day, she still hasn’t. Christiansen has been working for Scientific American for 19 years and currently oversees many of the data visualizations and explanatory graphics in each issue. Usually that means assigning projects to other researchers and artists. But this month she had the opportunity to craft many of the graphics herself, including visualizations of atomic clocks, salt-tolerant plants, creative intuition and our knowledge of knots. “It was a treat to be able to see [these projects] to the end,” she says.

Turning complex science into digestible graphics can be like a puzzle—and Christiansen finds the hardest ones the most rewarding. Those usually involve the fields of physics or chemistry, where “there’s very rarely anything for you to look at,” she says. But she’s also learned that even tangible, physical objects can stretch our intuitive abilities. In this issue’s Graphic Science column, written by space and physics senior editor Clara Moskowitz, Christiansen demonstrates how bad we are at judging the strength of knots. They’re “kind of like optical illusions,” she says, ones that defy our physical reasoning abilities—and remind her to “slow down and question” how people might interpret her illustrations differently than she does.