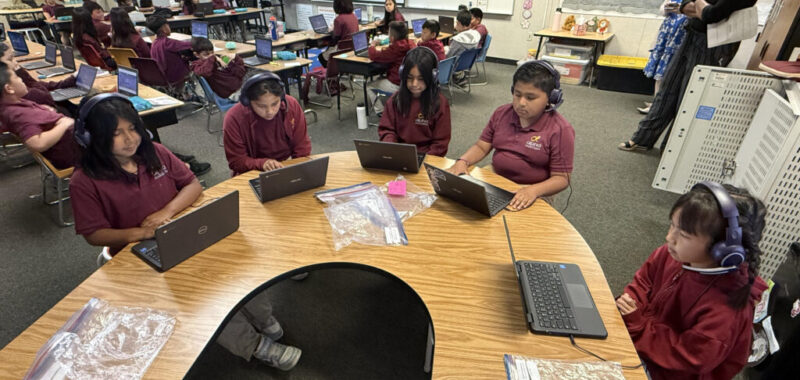

Third graders at Alpha Cornerstone Academy join their individual Ignite Reading tutors for their 15-minute daily session on phonics and other fundamental skills in reading,

John Fensterwald / EdSource

Top Takeaways

- Up to 40 districts and charter schools can sign up to design their own high-impact tutoring.

- Unless they’ve spent billions already, districts should have funding available.

- Both online and in-person high-impact tutoring will work can show impressive results – if done right,

A recent visit to Alpha Cornerstone Academy, a TK-8 charter school in San Jose, offered a glimpse of high-impact tutoring. It was during the intervention period in third grade, a time when teacher specialists work in small groups.

In one corner, five students in their maroon Alpha school shirts sat around a horseshoe table, listening intently through earphones to their own tutor from Ignite Reading, a growing Oakland-based public benefit corporation operating in 20 states. Ignite specializes in tutoring foundational skills – phonics and phonemic awareness. Each lesson was different; some students were repeating words with similar letter sounds. One girl, Sophia, was reading paragraphs to her tutor.

At the start of the year, 103 students were reading from kindergarten and first grade levels, said Fallon Housman, the school’s principal; some were newcomers to the school; others were English learners, fluent in their home language but needing extra time, and others have been identified as having a learning disability.

Now, with the school year coming to a close, all but 20 are reading at third-grade level, Housman said. Sophia is now among them. “I feel like it’s earlier to read,” Sophia said quietly.

“We see a lot of our third graders actually do really well towards the end of third grade because of all of the interventions and supports. We’re excited to have Ignite because it’s an extra push, focusing on foundational skills,” Housman said.

What’s happening at Alpha Cornerstone Academy classroom could be in many California districts. Unlike districts in other states that are scrambling for money to continue tutoring funded with now-expired federal Covid aid, California districts potentially still have multi-billion-dollar state funding for accelerating learning over the next several years.

And having watched tutoring elsewhere from the sidelines for the past four years, the state can avoid other states’ missteps and build programs based on their successes – if California makes tutoring a priority.

“Tutoring isn’t just a tool for learning recovery,” said Jessica Sliwerski, co-founder and CEO of Ignite Reading. ”It’s serving as an essential classroom support that students need to build strong literacy skills.”

A second or “Western” wave of tutoring

“Lots of other states have helped push tutoring along more than California has. I’m really optimistic that in some ways, it [California] can be a leader, because we’ve learned so much that they could really do it more effectively immediately than we could right at the beginning,” said Susanna Loeb, a professor at the Graduate School of Education as well as the founder and executive director of the National Student Support Accelerator.

Loeb sees an opportunity for California to jumpstart the state’s laggard performance on state and national achievement assessments, especially in early literacy, by creating a second or “Western” wave of tutoring.

In four years, the National Student Support Accelerator has become the foremost source of information on and coordinator of research into online and in-person “intensive, relationship-based, individualized instruction” called by various names, high-dosage, high-impact, or high-intensity tutoring.

This week, three state agencies – the California Department of Education, the State Board, and the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence – will make the first joint effort in promoting it. They will join the nonprofit Results for America, and Loeb’s organization in sponsoring a webinar explaining high-impact tutoring.

The May 13 event serves as an invitation for up to 40 school districts to design their own high-impact tutoring programs that could serve as a model for other district cohorts.

It isn’t clear what happens after the event, but tutoring providers are hoping the state will get more involved.

“This is the first time that the state has recognized high-impact tutoring as desirable. We know what the research has found; we know the formula for making tutoring work,” said Chris Norwood, founder of Bay Area Tutoring Association, which works with school districts on creating effective programs. “Now we have to get the word out through channels of information that districts use, like county offices of education.”

An exciting prospect, hard to do

Many parents, teachers, policy makers and student equity advocates looked at tutoring as a recovery strategy coming out of Covid.

“What was not so clear was whether they could actually pull it off at any kind of scale,” said Loeb who acknowledges it’s easier for smaller states with a less complex system of governance to say, “Here’s the guidance on how to do high-impact tutoring; here are some funds to do it, and here are professional support.”

The federal Institute of Education Services identified “high-quality” tutoring as one of several effective strategies for schools. An analysis of 96 rigorous studies comparing results of students who had high-impact tutoring with those who hadn’t found significant improvement in 87% of the programs, equivalent to a half-year growth in many cases. The strongest gains were in early grades in literacy and when it was given during, rather than after, school.

Based on research, the National Student Support Accelerator says that effective, high-impact tutoring programs have these elements in common:

- A high-dosage delivery of three or more sessions per week of required tutoring, each 15 to 30 minutes.

- An explicit focus on cultivating tutor-student relationships, with tutors assigned with the same students throughout. Consistency is critical to building a solid relationship, and the tutor should be “someone who is engaging and motivating,” Loeb said.

- Alignment with the school curriculum.

- Formalized tutor training and support.

- The use of formative assessments to monitor student learning.

There are different models for districts: training paraprofessionals as full-time tutors, hiring outside tutoring organizations for in-person tutoring, or turning to online nonprofits; the latter lack the face-to-face connection but can better scale up to serve more students, she said.

But many California districts found that creating a system with all of the elements was hard to pull off, and outside of urban areas and university towns, many had difficulty finding organizations and trained tutors for in-person instruction. Districts lacked experience evaluating tutoring outfits’ promises and measuring results. Communication over student results could be erratic; arranging schedules could be a challenge.

Given other, more familiar options, many overstretched California districts and schools made tutoring a low priority; they invested instead in hiring teacher aides and counselors.

An examination by Edunomics Lab, a Georgetown University-based education research nonprofit, found that 70% of California’s public school districts, charter schools and county offices of education didn’t report spending any money on tutoring from the last and biggest outlay of federal learning loss funding for California – ESSER III. Of the 30% of districts that did, spending on tutoring totaled 1.5% – $190 million out of $13.5 billion. (Go here for an interactive graphic on California districts’ tutoring spending.)

Meanwhile, other states became directly involved in high-impact tutoring. According to the National Student Support Accelerator’s 2024-25 summary of states’ activities, two dozen states allocated specific funds for high-impact tutoring, while others provided technical help to set up programs. One state, Tennessee, is funding tutoring through its annual school funding formula.

Nine states have ongoing partnerships between higher education institutions and tutoring organizations.

Norwood is partnering with San Jose State to hire students on an education track to serve as tutors in the schools while earning federal work-study money. If all teacher preparation programs credited time tutoring toward fulfilling time required in the classroom, California could add thousands of tutors to the ranks.

Money to spend

California had the advantage of surging state revenues from a post-pandemic economic boom to set aside more than $10 billion in one-time and ongoing money for schools in 2021-22 and 2022-23.

The state lists tutoring as one of the evidence-based options that districts can choose for their unspent share of the $6 billion Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant; they have through 2027-28 to use it. It’s not clear how much remains; districts filed the first spending report in late 2024.

There’s also the $4 billion Expanded Learning Opportunities Program, although that money can only be used before or after school and during summers (Rural districts argue there needs to be more flexibility for tutoring).

The advent of universal transitional kindergarten next fall and rollout of a new math framework are touchpoints for high-impact tutoring, Loeb said.

“If I had to think about where California could embed tutoring just as part of normal operations, it would be in early literacy,” she said. “It is a shame and a detriment to the state that so many students are not learning how to read before third grade. There’s lots of evidence that high-impact tutoring can help get us there.”

The selection of new materials aligned with the math framework will lead districts to rethink how math is taught.

“That’s a really good time to say, ‘OK, within this structure, how do we get students who aren’t making progress at the rate of the class or rate the state expects to get that individual attention so that they can accelerate their learning and excel in school?’ We’re not really doing that, so students are kind of falling off as we move quickly through the curriculum.”