Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation, 1344, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The last time I was in Siena there was an earthquake. The first time I was nineteen. My boyfriend, who had already graduated from college, had been in Italy most of the year, in Perugia. The plan was to take an intensive course in Italian—he wanted to read Dante—but then he discovered a passion for painting. Could it have been the day after I arrived that we took the train from Perugia to Siena? Even now, from Perugia, one changes train twice, first in Terontola, and then at Chiusi-Chianciano Terme, a station that decades later would become familiar, arriving in the Val D’Orcia from Rome, and where one afternoon we sat deathly ill in the station bar, beset by what—an ability to go on? But then everything was new.

In Umbria, the landscape is mist and the hills are often in shadow, the luminous inner life is a long let-out breath, but as the train trundles into the province of Siena, the light sharpens like a scalpel, and the shadows disappear. The usual bustle at the station. Then, a stone’s throw from the Duomo and the Piazza del Campo—which erupts in July with the running of the horses in the Palio—the Pinacoteca Nazionale is housed in two adjacent palazzos. On four floors, it holds the most important collection of Sienese paintings in the world. The core of the collection was assembled by two abbots, Giuseppe Ciaccheri and Luigi de Angelis, painting by painting, between 1750 and 1810. They knew, somehow, that these unfashionable, strange, mystical, transfixing pictures, which hovered between Byzantine art and abstraction, painted in the margins of the history of art, many salvaged from triptychs and altarpieces that had been sold, dismantled, or lost, were worth saving.

On that first visit the galleries were nearly empty. I had been brought up on twentieth-century painting—my grandfather had taken me on Saturday mornings to what was then called the Modern, but I had very little idea of painting as narrative. The only picture I knew that had the quality of continually happening in time was Picasso’s Guernica. But that is another story. Here in Siena was one chapter after another of a different story: the Annunciation, the Madonna and child, miraculous episodes, the Cross, the eternally mystifying Second Coming, the Assumption. There were the perplexing lives of the saints. Each figure was aglimmer, as if these narratives were continually occurring, unfolding even then as we looked on. My own understanding of these stories was limited—it amounted to being taken to see the Christmas windows on Fifth Avenue and listening to my father sing carols in the car. But I knew, even as I arrived from that distance, that these paintings from the trecento were ones to which from now on my attention would be directed. Later, when my first child was born—who grew up to become a painter—one of the first places I took her was to see the Italian paintings at the Met, where she fixed her eyes on the gold light.

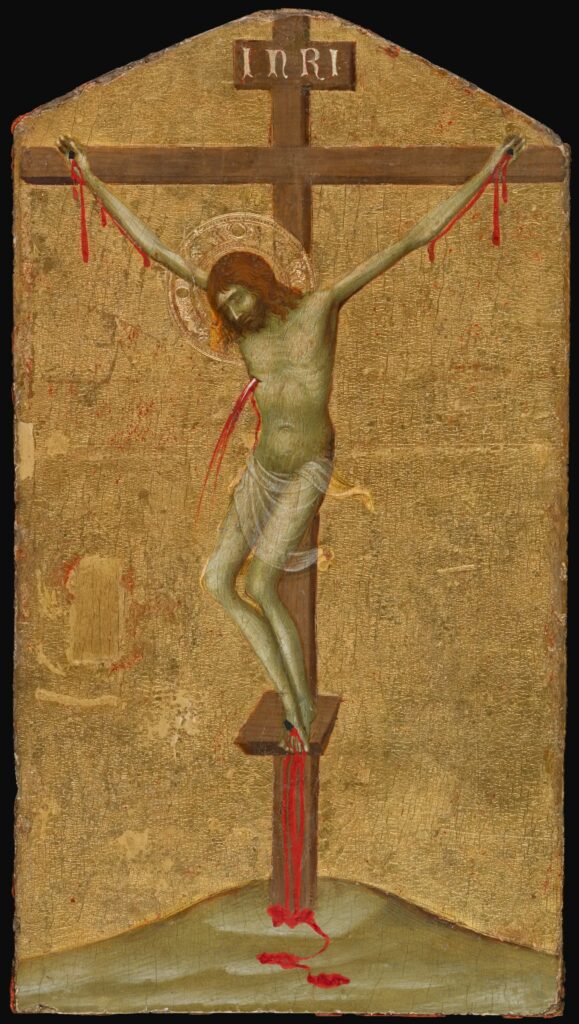

But that day, it was perhaps no accident that my favorite painting was a small green panel by Stefano di Giovanni, later known as Sassetta, of a traghetto, its hull like the inside of a peapod, pulled up to a bank beside a castle. It was one of the only—and earliest—representations of a secular subject in the galleries. That fall, when I returned to school, I found myself often at the university art museum, where I went to look at a tiny crucifixion by Simone Martini, painted sometime between 1315 and 1344. I cannot say exactly what drew me to it. The Christ figure, emaciated, is nailed to a simple wooden cross. No one else is there; it is a scene of complete loneliness. Blood spurts from Christ’s side, drips down his emaciated arms, and cascades from his feet down the base of the cross. The background is gold leaf, layer upon layer, so that the scene is entirely irradiated with light. It was my last year at school. Why this scene of horror comforted me, as I was about to step out into the world, I cannot say, but the painting was alive to me with the hand of its maker.

In the current Met exhibition Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350, very few of the paintings are borrowed from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena or even from Siena at all, but the ones that are include the Ambrogio Lorenzetti annunciation, in which the Virgin, surprised at her book, fixes her perplexed gaze on the dove rather than on the angel. There is also the exquisite Maestra, by Duccio, painted in his workshop on the Via Stalloreggi, steps from the Duomo, which stayed in place in there until 1771, when it was dismantled. But most of the paintings and objects have been brought together for the first time in hundreds of years, from museums in the U.S. and across Europe.

Of these masterpieces, among the most striking, at least in terms of scale, is Pietro Lorenzetti’s Tarlati polyptych for the Church of Santa Maria della Pieve in Arezzo, in which the saints, going about their business, are framed by arched windows on three stories. In the Met’s dimly lit room, looking at the gigantic polyptych is like gazing into an apartment building at night, where the tenants, not knowing they are observed, can be seen conducting their discrete business of life on earth. At the center is Mary in a white gown and hood embroidered with rosettes, perhaps putting the plainly garbed Christ child to bed. On the upper and lower stories are a score of saints, the usual suspects—among them John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, and Saint Matthew—and four women who were Christian martyrs: Catherine of Alexandria, Ursula, Agatha, and Reparata, who was saved from being burned alive by a shower of rain. The Sienese artists painted the saints from models they knew—their sisters and mothers, men and women who lived down the street, and then, over decades, the children of these men and women. Those faces, both mysterious and familiar, are held here by time’s gaze.

This show, which includes one hundred–odd paintings and objects, is so luminous that it is difficult for a viewer to comprehend that the assembled works were made over the course of just fifty years. At the end of this apotheosis, from 1346 to 1353, the black plague drew its deadly brush across Europe, killing almost fifty million people, including most of these painters and the models for these paintings. Just a few years ago, would we have had any idea what that meant? It is always news that we can go on. It may be part of the solace of this brilliant show.

When I arrived at the last room of the exhibit, I realized I was looking for something. I turned, and there it was, the crucifixion by Simone Martini, which I’d spent so many hours looking at in Cambridge long ago. I saw now that there was a smudge of gold leaf on the left side of the cross—was it a figure the artist blotted out? A friend who writes about the history of art believes that paintings have their own experiences across time, as we do, and that those experiences become part of the paintings. Perhaps this is so.

Simone Martini, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1340, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0 4.0.

According to an essay by Stephen Wolohojian, in the amply illustrated book that accompanies the Met exhibit, Ambrogio Lorenzetti was among the great storytellers of the fourteenth century; he was a teller of secular tales, as well as sacred ones. Lorenzetti’s work, and his brother Pietro’s, are represented here, but one of the masterpieces in Siena, which did not travel to the Met, is Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government. This hangs in the Sala della Pace (the “peace room”) of the Palazzo del Popolo, Siena’s town hall, where the nine elected city magistrates once conducted civic business.

On that long-ago visit to Siena, we made our way from the Pinacoteca to the Palazzo Popolo, where the Lorenzetti frescoes cover three huge walls and portray the effects of good and bad government in the countryside and the city. In the first instance, the vision of good government is ruled by Faith, Hope, and Charity. (According to Ruskin, writing about the frescoes in 1870, Hope, who crowns the benign leader, is the most important of these virtues, which may be something to keep in mind.) But in the latter, scarifying images, pestilence ranges in the fields; in town, the ruler wears a devil’s crown, and keeps a Cerberus as a pet. Like the meticulously illuminated tribulations of the saints, the murals—with Lorenzetti’s strange, Edward Gorey-like figures and his weird dragonfly angels—were meant to instruct. As we looked at them then, I saw, as if transposed by a stereopticon slide onto the maleficent landscape, Picasso’s rearing horses which had transfixed me as a child. That summer, Dante accompanied us. “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, mi ritrovai per una selva oscura, che la diritta via era smarrita,” M. read aloud.

Lorenzetti’s frescoes, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CCO 3.0.

The last time I was in Siena, on a hot day in June, it was cool in the museum. I’d found Sassetta’s painting of the tranquil boat pulled up to tranquil bank when from outside the building came the sound of a tremendous crash, as if two trucks had collided on the Via San Pietro. The floor swayed. Un terremoto! exclaimed the museum guard, gesticulating wildly towards the stairs. Un terremoto! Andare fuori, andare fuori! With the other bewildered museumgoers we were hustled down the stairs and exited the building, where on the narrow street a gaggle of tourists, unimpressed by the tremor, wandered by eating technicolor gelati.

I had planned to visit the Lorenzetti frescoes after the morning in the Pinacoteca, but because of the earthquake, which registered 3.7 on the Richter scale, and whose epicenter was ten miles away, in Poggibonsi—the Duomo, even the great apron-shaped piazza where the horses were due to run in a week’s time—were immediately shut so that structural damage could be assessed. I was sorry not to see them. But I think I knew then, with foreboding, that like so many stories that accompany us, waiting to go on, flapping their bat-like wings until the curtains part, I would see Lorenzetti’s allegory again—if not in Siena, then closer to home. What to do? Everything was closed. We walked up the street in search of a cold drink, and as in the lucent paintings of the trecento, the slant light turned the streetscape two-dimensional and the brilliant sun left no shadows.

Cynthia Zarin’s most recent books are Inverno, a novel, and Next Day: New & Selected Poems. Her second novel, Estate, is forthcoming. She teaches at Yale University.