January 3, 2025

3 min read

Heliophysics Is Set to Shine in 2025

The science of the sun and its effects on the solar system is a sprawling discipline that expects a very exciting 2025

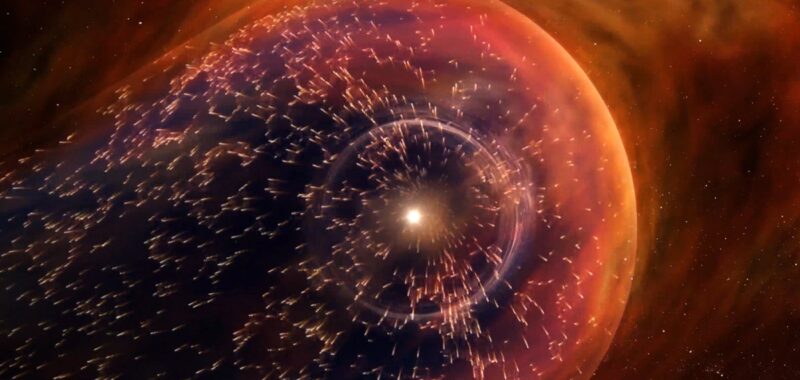

The sun sends out a constant flow of charged particles called the solar wind, which ultimately travels past all the planets to some three times the distance to Pluto before being impeded by the interstellar medium. This forms a giant bubble around the sun and its planets, known as the heliosphere.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

If our solar system were to lose a few moons or even a planet, the difference might be hard to notice—but lose the sun, and everything changes. Despite its role as neighborhood linchpin, however, scientists still have a whole host of questions about how the sun works and how it influences our daily life on Earth and in space. And 2025 is poised to play a key role in getting answers.

Three factors are combining to make the coming year particularly exciting for the discipline known as heliophysics: the sun’s natural activity cycle, a fleet of spacecraft launches and the release of a blueprint designed to guide the next decade of work in the field.

Right now the sun is in the maximum phase of its 11-year activity cycle, where scientists expect it to remain for perhaps another year or so before its activity begins to wane. And although the current Solar Cycle 25 isn’t breaking any records, it has produced a host of solar flares and other spectacular outbursts that scientists have been able to monitor with recent new instruments. Those observers include both the largest solar telescope ever built and a spacecraft that has made the closest approach to the sun in history.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

And this year those groundbreaking projects will get plenty of new company; NASA alone expects to launch half a dozen missions to study the sun and the myriad ways it shapes the solar system. Among them are the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, or IMAP, designed to help scientists map the outer limits of the sun’s sphere of influence; the Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers, or ESCAPADE, a pair of spacecraft that will orbit Mars to study the Red Planet’s experience of space weather; and the Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere, or PUNCH, mission, which combines four small satellites orbiting Earth to study the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona.

Moreover, U.S. heliophysicists have a new so-called decadal report, a blueprint for the coming decade that sketches out a host of national science priorities, that was released last month and that federal agencies will begin implementing in the coming year. “I’m really excited about it,” says Joe Westlake, a heliophysicist and director of the Heliophysics Division of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.

“These decadals are aspirational views of our future,” he says. “There’s some really good stuff in this one.”

For future spacecraft missions, the report recommends that NASA pursue two large projects. One mission would consist of a total of 26 spacecraft: Two would be stationed high above our planet’s poles in circular orbits and would take images of auroras and Earth’s magnetic field from afar. The rest would be located in more elliptical orbits that pass through the geomagnetic field, where they would gather local observations of its strength and nearby plasma. “Twenty-plus spacecraft and the ability to put those all together at the same time, looking down, looking up and collecting observations, is going to be such an incredible dataset tool for us,” says Nicki Rayl, acting deputy director of the Heliophysics Division. “I think it’s going to be groundbreaking.”

The second large project would be a spacecraft designed to swoop over both poles of the sun several times over the course of an entire 11-year solar activity cycle. A current NASA mission, the Parker Solar Probe, has been diving ever closer to the sun’s surface, but it has stuck to observing the sun over its equatorial region. Meanwhile an ongoing European Space Agency mission called Solar Orbiter has provided only partial views of the solar poles. Consequently, our star’s poles remain mysterious regions, even as they play a key role in the evolution of the sun’s magnetic field. “Going to the poles of the sun is hard, and it’s a tricky environment to get into,” Rayl says. “That’s the next unknown territory.”

On Earth, these ambitious missions would be augmented by the Next Generation Global Oscillations Network Group (ngGONG), which builds on the existing GONG group of observatories that began work in 1995. These observatories are spread around the world to keep the sun in their sights throughout the day, and they use a technique called helioseismology to study the solar interior by observing waves passing through it, much as geologists employ seismology to study the interior of Earth.

“Some of these audacious, incredible goals that are in the decadal help us really jump into the unknowns and do some discovery science,” Rayl says. And in the meantime, she notes, the missions launching in the coming year will yield ever more insights—and new questions to ask—about the sun. “I’m just thrilled that we’re going to be in the data-collection mode,” she says. “It’s go time.”