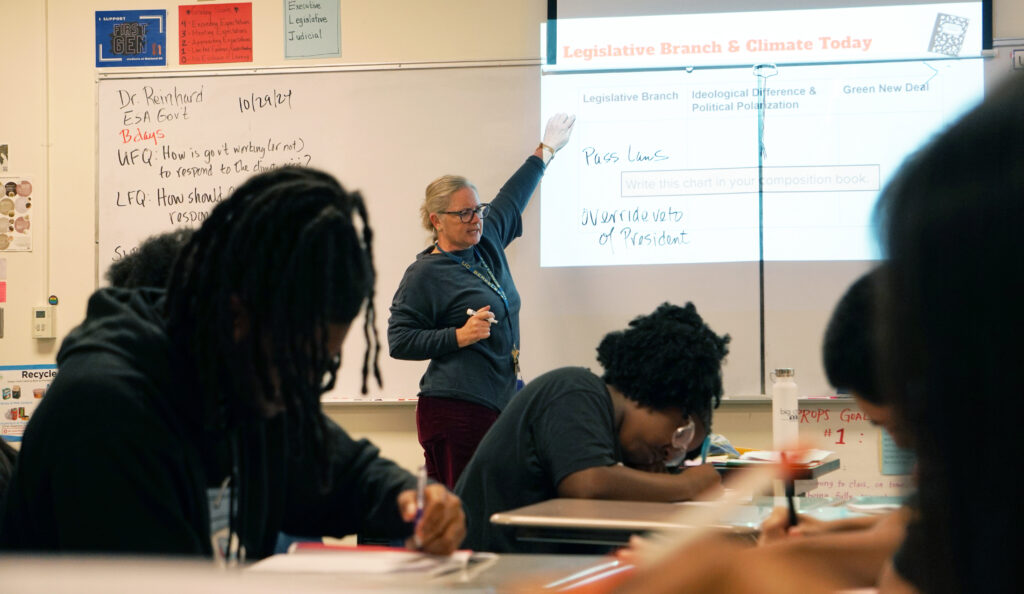

Oakland High teacher Rachel Reinhard guides her students through the functions of the legislative branch during a U.S. Government class last week.

Credit: Andrew Reed / EdSource

In the months preceding this week’s election, some California history and social studies teachers have proceeded cautiously in covering the presidential campaign, while others have embraced the opportunity confidently and comprehensively. But most included instruction about the presidential election in their courses, according to responses to an EdSource survey of California history and social science teachers.

Their responses underscore that most teachers understood the potential pitfalls of teaching politics in polarized times, compounded by a contagion of misinformation on social media. (Go here to read the questionnaire.)

“A lot of kids are turned off about government and politics. We in the classroom are giving them a sense of access and empowerment,” said Rachel Reinhard, who teaches 12th grade U.S. History and Government at Oakland High School. “We’re showing that elections are ways that individuals can exert power on the system and make sense of an incredibly fast-paced and changing world.”

Yet some teachers have struggled to explain how Republican Donald Trump’s rhetoric, threats of retribution, and vows to expel undocumented immigrants have added anxiety to an unprecedentedly tense and divisive election.

“The dilemma for any responsible teacher right now is to explain the stakes while being nonpartisan,” said Mike Fishback, who teaches seventh- and eighth-grade social studies at Almaden Country Day School, a private school in San Jose.

The California Council for the Social Studies agreed to send EdSource’s survey to its 2,000-member email list, which includes more than 500 active members, most of them teachers. Of those, 64 teachers — about 1 in 8 member teachers — returned the survey by the Oct. 16 deadline. EdSource did not require teachers to submit their names or their schools, although 16 teachers did identify themselves, and many said they were willing to be contacted for an EdSource article.

Among the top-line results of the survey:

- More than three-quarters of teachers who answered the survey said they are teaching about the election and the presidential campaign, and most of those who aren’t said it was their choice, not a district mandate.

- Asked if they planned to discuss the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol, 37% said no, 29% said yes, and 34% said maybe.

- Asked if they planned to discuss potential election interference, 39% said no, 23% said yes, and 38% said maybe.

- Asked to express their level of concern about student incivility in dealing with the election, 44% said they were slightly or not at all concerned; 23% said they were somewhat concerned; and 15% said they were moderately, very or greatly concerned. An additional 19% said they were neutral on the issue.

Inoculating for incivility

Creating a classroom culture of respect is critical to promoting openness and avoiding disrespect amid disagreements, Barrett Vitol, a U.S. History and Government teacher at Aptos High in Pajaro Valley Unified, told EdSource. He characterized the district as politically and economically diverse with “extreme wealth and hard poverty,” where some students in farmworker families “are genuinely worried” about the outcome of the election.

“When we come together in August, we spend a lot of time helping to build community,” said Vitol, who said he shares with students his own experience as a volunteer for the 2000 Democratic presidential campaign for then Vice President Al Gore.

“You have to role model someone who will be politically active without disrespecting other people,” he said, adding that he also relies on humor to defuse tensions.

Bob Kelly, a U.S. History and Government teacher at the 500-student Minarets High and Charter High School in Chawanakee Unified, also set class norms early in the year, with a “social compact that holds the students accountable to being respectful to each other,” he said. The rural school district abuts Yosemite National Park.

Bruce Aster, who teaches U.S. Government at Carlsbad High School, said that his goal “is to teach civil discourse from day one.” He tells his students, ‘If you demonize your opponent, you will not get their ears.’ That’s a big theme in all my classes.”

Many of the teachers cited guides and resources they drew on to promote civil dialogue, bridge differences of opinion and lay out frameworks for discussions. Popular sources include Braver Angels, a volunteer-led national nonprofit, and Boston-based Facing History and Ourselves, which offers lessons, explainers and activities on teaching the election.

While sources of misinformation have proliferated on the internet, so have tools to expose them. Teachers pointed to sites like adfontesmedia.com, AllSides.com and mediafactcheck.com that analyze news sources’ reliability and point to alternative sources with different political perspectives.

Reinhard refers to encouraging students to seek trustworthy and accurate news sources as building a “muscle memory.”

“I am hoping they would create a habit to counter what they are seeing on social media,” said Reinhard, who is in her second year teaching high school in Oakland after serving as director of the UC Berkeley History-Social Science Project; it supports K-12 teachers in planning for history instruction.

Karen Clark Yamamoto, who chairs the history department at Western High in the Anaheim Union High School District, said students found the revelations of bias in their favorite sites enlightening. “They realized, ‘I don’t know as much as I thought I did,’” she said.

To help students clarify their own political views, several teachers had students take the Pew Media Typology Quiz, whose questions reveal whether students have conservative or liberal philosophies.

Classroom priorities and strategies

The EdSource questionnaire asked teachers to describe the focus of their instruction and their plans for covering the election. The consensus was that a teacher should give students the tools to make informed choices about candidates and ballot issues.

James Yates, a teacher at Stellar Charter School in Redding, wrote, “I will teach my students how to investigate each candidate. I want them to look past the rumors and prejudice to see who will really help our country thrive.”

Kelly wrote, “We focus on helping the students make sense of the offices, candidates and propositions by understanding which issues matter to them the most.”

“Essentially, we focus on students informing themselves and using their own ideology to decide what is best,” said Jon Resendez, a U.S. Government and Economics teacher at Portola High in Irvine Unified. He has found that students, unlike some of their parents, are open when forming their political beliefs.

“It’s normal for teenagers to be more flexible than adults in their perspective as they learn more,” he said. “They adjust their voting behavior.”

Little outside criticism

Slightly more than a third of teachers responded to the question about whether they had experienced any criticism from teaching about the presidential election. The majority — 16 of 23 — said they had not, but five reported being criticized by parents, three by students and two by administrators or other colleagues.

All eight teachers EdSource spoke with said they were unconcerned about parental pressure or criticism.

“No parents are reaching out to express concern,” said Resendez. “Parents assume we will tackle issues head-on.”

Kelly, of Chawanakee Unified, uses his students’ work to inform parents about the elections. His students created election guides that they shared at the school’s back-to-school showcase in late October. It included separate objective profiles of Democrat Kamala Harris and Trump, drafted by students chosen because they didn’t support the candidates, Kelly said, along with summaries of local candidates and statewide ballot propositions.

At his back-to-school night, Fishback, of the Almaden County Day School in San Jose, encourages parents of his middle school students to discuss election issues and candidates with them.

He said that he tells them, “’I need you. If you have not passed along your political values, now is the time to do it. I want them to come to class knowing what families believe and why. My job is to help the students encounter and engage with different perspectives on a variety of contentious issues.’ ”

What the teachers taught and how

The survey asked teachers to check off a list of topics for presenting the presidential election and to add to it. Of 48 teachers who responded to the question, 37 said they reviewed candidates’ positions on key issues and 35 discussed the Electoral College; 28 asked students to explain issues that are important to them and 23 included fact-checking candidates’ claims and statements. Fifteen said they discussed claims that there would be widespread voter fraud.

One teacher included discussing gerrymandering, and another said classes would focus on differences among political parties but not the candidates themselves.

The teachers reported that they approached the topics with different strategies. Some had students participate in the traditional statewide mock election organized by the California Secretary of State or held their own elections. Some teachers held candidates’ debates, while others intentionally did not, focusing instead on objective analyses of candidates’ positions and the accuracy of media coverage.

“I’m not interested in debates,” said Reinhard of Oakland High. “Debates often create false parity. I’m not interested in having students try to win a debate around some information I find problematic.”

Yamamoto asks her students in Anaheim to pick five issues they care about and investigate the positions of the parties and the candidates’ websites to determine which party more closely aligns with their views. Inflation, health care and reproductive rights were among the issues. They did the same process with the 10 state initiatives on the ballot.

Barrett organized a model Congress for his students at Aptos High. Students wrote their own bills and had to persuade committee chairs and each legislative house to pass them. “Extreme” bills on immigration didn’t make the cut; those that did pass include creating affordable health care, limiting homework, requiring those over 70 to take an extra diving test, taxing billionaires, and granting immigrants who pay taxes for five years a path to citizenship, he said.

Some students become deeply invested in their bills, but usually they can control themselves, Barrett said.

Aster, of Carlsbad, and Kelly, of Chawanakee Unified, continued what they have done for years: bringing in outside speakers to represent parties and candidates for a debate run by students. “We seek regular folks, not politicians,” said Aster. “It’s always civil, and students see that you can be gracious while speaking strongly.”

Several teachers said they didn’t avoid controversy, including looking at the rhetoric of the campaign: Trump’s racist language and post-election authoritarian threats and Democrats’ calling him a “fascist” and a “clown.” But students looked at the furor through an analytical lens to keep discussions “from going off the rails,” said Fishback. He asked his students, How would you characterize Trump, and what has been the impact of his language on the campaign?

Most teachers emphasized they kept their own presidential preferences to themselves. “I work hard to be objective; I want it to be a mystery as to my views, though I don’t want them to think I don’t care,” said Aster. Kelly said he would tell students after the election whom he voted for if they asked.

“As much I like to lean into politics, the line I don’t cross is siding with one candidate over another,” said Fishback.

Seeing themselves as voters

Aster has been teaching high school for more than three decades.

“I see part of my job is to be a cheerleader for the American system and to have them look forward to participating in it,” Aster said. “I don’t want them to come away thinking the system is rigged.”

Last spring, when it appeared likely to be Trump vs. Joe Biden, students in Reinhard’s Government class at Oakland High had no interest in the election. “They were deadened by it,” she said. The nomination of Harris, the hometown candidate and a younger woman of color, however, at least sparked interest, she said.

More findings in the EdSource Questionnaire

- The teachers were from all regions of the state, with 27% from Southern California, 17% from the Central Valley and Central Coast and 17% from the San Francisco Bay Areas, 14% from the Sacramento area, 10% from Northern California, 9% from the San Diego area and 3% from the Inland Empire of San Bernardino and Riverside counties.

- Of the teachers who said they aren’t teaching about the presidential election, only three – two who teach in a largely Democratic district and one from a largely Republican district – said it was their school’s and/or district’s policy not to discuss the subject. Another teacher is discussing the election but not the candidates.

- Offered multiple choices to explain their reasons for not teaching the election to their students, the majority said there is too much other course material to get through, especially AP courses in U.S. History and Economics and one semester in Government. However, one-third of the 24 respondents to this question said they were concerned about complaints from parents, and five teachers said they had reservations that students would discuss the election respectfully. Five teachers said they were unsure how to address the subject.

- Teachers were evenly split on how much time to spend on the election, with 39% of 49 respondents spending more than one week on it and 39% spending between two days and a week. Several said they spread discussion of the election out over time, based on topics in the courses they were teaching, and another teacher said five to 10 minutes per day.

- Most of the respondents were high school teachers who teach multiple subjects; 43% introduced the election in a 12th grade Government course, while 42% taught it in 11th grade American History; 27% taught it in 9th grade Ethnic Studies and 25% introduced it in 10th grade World History. A quarter of respondents were middle school social studies teachers. Individual teachers taught it in AP Psychology, ninth grade Geography, and an English course in persuasive essays.