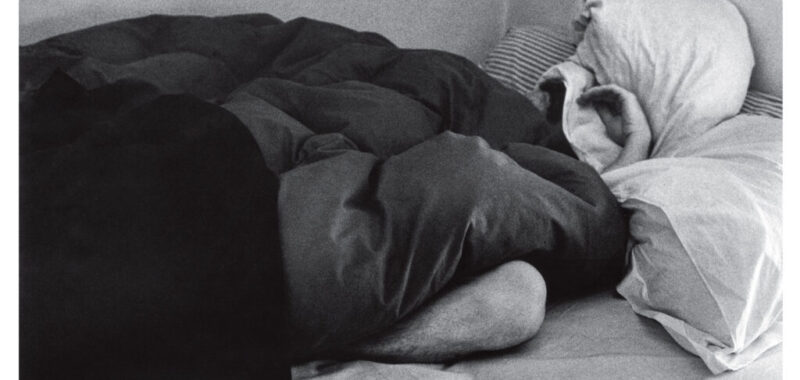

In one of Sophie Calle’s first artistic experiments, she invited twenty-seven friends, acquaintances, and strangers to sleep in her bed. She photographed them awake and asleep, secretly recording any private conversation once the door closed. She served each a meal, and, if they agreed, subjected them to a questionnaire that probed their personal predilections, habits, and dreams. The following text is Calle’s narrative report of her third guest’s stay, and is the first in a series of four excerpts from the project to be published this week on the Daily.

I do not know him. A mutual friend gave me his contact information. I call him and tell him briefly about my project. He is hesitant. First, he wants to know if I have a bathtub. He wants to sleep ten hours, at night only. Finally, he agrees. He will come Monday, April 2, from one to ten in the morning.

Monday, April 2, Bob Garison arrives at the agreed-upon hour. After the two women who preceded him leave, he takes a seat in the dining room. He accepted the principle of the game but has difficulty submitting to the ritual. He wants to “make himself at home.” He delays the moment of getting into the bed. He says he’s in no rush.

I do not want to call into question the proceedings of the experiment, its reasons, its rules, but how can I explain the importance of this bed being continuously occupied to a man who disregards the necessity of it. I let him do as he pleases.

He decides to take a bath. He leaves his clothes on the floor. (During the night, I rummage through his pockets, for no reason, just to rummage. They are empty. Then I gather and carefully fold his clothes.)

At two in the morning, he finally gets into the bed. I propose that he answer a few questions.

Can he give me a brief description of himself?

“Okay. Robert Garison, thirty-two years old, American, trumpeter.”

Is sleeping a source of pleasure for him?

“It’s one of my primary activities.”

Does the door need to be open or closed?

“Doesn’t matter.”

Does he talk in his sleep?

“I don’t think so.”

How does he think he sleeps?

“I don’t think about it.”

Does he use an alarm?

“They should be banned.”

Does he have a difficult time waking up?

“Not difficult, but it does take me an hour or two to wake up.”

Does my presence in the room risk disturbing his sleep?

“That depends on you, if you’re noisy.”

Does my gaze risk disturbing his sleep?

“The gaze alone? No.”

Does he ever disguise himself for sleep?

“No! Why? Are there people who disguise themselves? As what?”

Has he ever participated in an experiment of this kind?

“No.”

Can he tell me a fond memory of sleep?

“No.”

Can he tell me a bad memory of sleep?

“Probably, a night when I was kept from sleeping, for example, on the overnight train to London. That train is always annoying.”

Does he dream?

“Yes, I remember my dreams as soon as I wake up but forget them for eternity if I don’t engage with them in some way after.”

Why did he agree to come?

“Curiosity. I like meeting people.”

What does he think of the people who preceded him?

“Very nice. Am I supposed to think something? Yes, they were very nice, but I don’t know why they were together. Do they normally sleep together, those two?”

He adds, “I appreciated the bath too. What bothered me was that I didn’t want to be forced to arrive at a specific time, to sleep right away. I don’t schedule my time like that. But it worked out.”

What would he like for breakfast?

“Do you have an espresso machine? No … okay, I’ll take a coffee and a pain au chocolat. Does that work?” He adds that he likes to flip through the Herald Tribune in the morning.

At 2:30 A.M., I leave him. I did not dare ask him any more intimate questions. This is my first unknown sleeper. I lack the audacity.

During the night, I photograph him several times. He moves very little. My presence does not seem to disturb him. At ten, I wake him up by taking a photo. I bring him his coffee. I forgot the pain au chocolat and disregarded the newspaper. He wants to get up immediately. He does not ask my permission. The young woman who should take over, Maggie X., does not show up, and he refuses to wait. While he is here, the bed remains unoccupied for a long time. Going forward, I’ll be more firm.

At 10:30 A.M., I walk him to the door. I thank him for coming over to sleep.

I call Maggie’s place and learn that she has just gone to bed. She must not be disturbed. I contact my mother who lives at the end of the street. She agrees to come over right away.

From The Sleepers, to be published Siglio Press in December. Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan.

Sophie Calle is an artist, writer, photographer, filmmaker, and performer whose work often makes use of Oulipian constraints. A retrospective of her work, Overshare, is currently on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.